When cost models hit the wall clock

When analysing algorithms, we use a cost model that assigns an abstract “cost”. For sequential algorithms, we usually count some notion of evaluation steps, which we denote as the work of an algorithm. For parallel algorithms, this is not quite sufficient: apart from the total amount of work, we also care about which steps are independent, and therefore can be executed in parallel. We denote by the span (sometimes depth) of an algorithm the longest chain of sequential dependencies. Intuitively, this is how much time it would take an infinitely parallel computer to execute the program. During presentations of the final projects for our recent course on Data Parallel Programming we had some interesting discussions about whether the promises of Futhark’s cost model actually holds water in certain edge cases, which inspired this post.

Costs of certain operations

As an example, Futhark’s map when applied to an array with n elements is

defined to have a work of O(n), when we asume the cost of executing the mapped

function is constant. Since each iteration of the map is completely

independent, we say that the span is O(1).

In contrast, consider summing an array. One approach is to to pair up

neighbouring elements and add them together, producing an array of half the size

as the original. If we assume for simplicity that the original array has a size

that is a power of two, then we can repeat this process O(log n) times,

leaving us with an array with just a single element, which contains the sum of

the elements of the original array. Therefore, we say that summation (and the

more general notion of reduction) to have span O(log n). The Futhark

compiler does not actually use this halving approach for its implementation of

reduce (it does some chunking to improve

locality),

but it does promise O(log n) span, which is optimal.

A cost model is a theoretical construct, and we can promise whatever we want. The problem, of course, is that cost models are contracts, and it is generally easier to make promises than to keep them in your implementation. While most parts of Futhark’s cost model are pretty conventional and uncontroversial (we don’t want to pick fights with semanticists, as they can be quite ruthless), there are some cases that I am not so comfortable with.

One place, in which we are arguably playing with fire, is that plain array indexing is O(1). This is inherited from the RAM model, which is still a fairly commonly used cost model, although clearly it is not quite accurate in the presence of modern memory hierarchies. It can also be argued via the mass-energy-information equality principle that in a fundamental sense, the more data you have, the more physical space it must take up, and hence the slower it is to access in the worst case. However, on a real machine, the sequential RAM model is usually good enough for asymptotic analysis, even if it cannot be used to justify locality optimisations.

But apart from random access reads, Futhark also supports random access

writes through the scatter function. With scatter, you pass a destination

array, an array of indexes, and an array of values, and get back a modified

array (with referential transparency preserved through uniqueness

types, but that is an orthogonal issue). In

Futhark’s cost model, scatter has O(n) work (in the number of elements to be

updated) and O(1) span. Further, there is the requirement that you may not

write different values to the same index, but you may write the same value

multiple times to the same index. It turns out this can be used to play some

asymptotic complexity trickery that perhaps the Futhark compiler cannot really

justify.

Playing some asymptotic complexity trickery

Consider the problem of determining whether an array of booleans contains at least a single true value. When this crops up in practice, we usually have an array of some other type and want to know if any element satisfies some predicate, but we’ll consider the simpler case of an all-boolean array. We can write this function as follows, using a reduction with the boolean or-operator:

def or_reduce [n] (xs: [n]bool) = reduce (||) false xsThe work is O(n) and the span is O(log n). However, we can also write it

with scatter, where we take advantage of the fact that scatter ignores

writes that would be out-of-bounds. The trick is to scatter into a

single-element array, and turn non-true values into invalid indexes:

def or_scatter [n] (xs: [n]bool) =

head (scatter [false] (map (\x -> if x then 0 else 1) xs) xs)By Futhark’s cost model, this function has O(n) work, but only O(1) span,

meaning it should in some sense be faster, or at least scale better. Yet I am

deeply suspicious of this, as it is essentially a many-to-one communication,

which does not intuitively seem like it should be constant to be. Also, the GPU

code that comes out of this will consist of many threads writing to the exact

same spot in memory. This will work, because they all write the same true

value, but I imagine the memory system will have to do some kind of

sequentialisation of the different transactions.

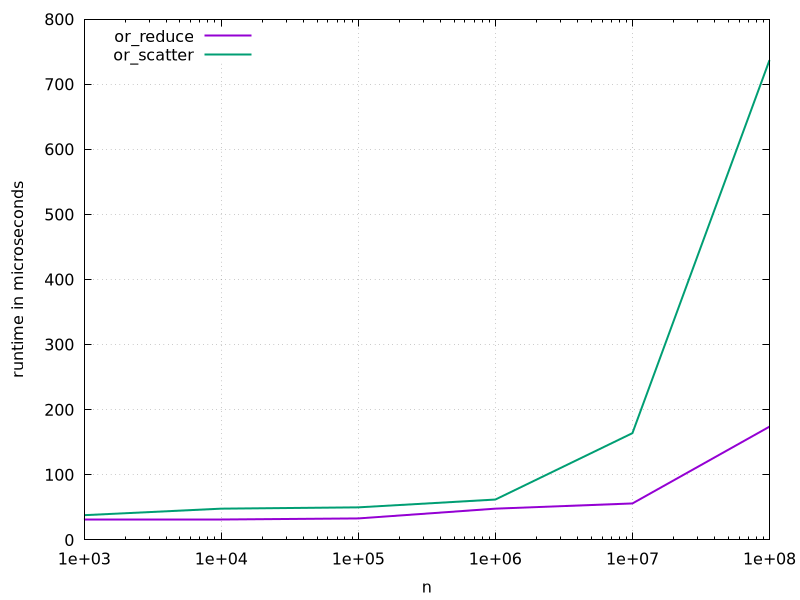

So why don’t we check what happens if we actually implement this and benchmark it on some random arrays of booleans? I did so, ran it on one of the A100 GPUs at the department, and got the following results.

While they start out pretty close, clearly the reduce-based implementation

works better for what is, fundamentally, a reduction. I tried playing around

with the input distribution, in particular the case where only a single input

element has a nonzero value, and while it did produce an almost 2x speedup for

or_scatter, that is still not enough for it to match or_reduce.

This suggests that while Futhark’s cost model needs some refinement. While span

complexity does not translate directly to wall-clock performance on account of

me not being able to afford one of those infinitely parallel computers on a an

academic salary, I am not comfortable with the current promises for scatter.

Perhaps a better complexity guarantee is that the span is proportional to the

number of writes to the same index. This might also be an avenue towards

improving our complexity guarantees for generalised

histograms,

which we currently document as having an extremely pessimistic linear span, to

account for a very rare worst case where you have a huge but very sparse

histogram where all inputs update the same bin. Our students always end up

hyperfixating on this because it messes up the complexity of their programs that

use histograms, despite the students actually writing a work-efficient

logarithmic span implementation of generalised histogram as part of their first

assignment

(but which we do not use in the compiler because its constant factors are much

worse in all non-pathological cases).